|

Service Record

|

From

|

To

|

|

Kinnaird Castle

Cadet

|

1/1971

|

6/1971

|

|

Clan MacGregor

Cadet

|

7/1971

|

8/1971

|

|

Clan Sutherland

Cadet

|

8/1971

|

9/1971

|

|

Nina Bowater

Cadet

|

9/1971

|

11/1971

|

|

Hector Heron

Cadet

|

12/1971

|

4/1972

|

|

Clan MacInnes

Cadet

|

1/1973

|

1/1973

|

|

Clan MacIntosh

Cadet

|

1/1973

|

7/1973

|

|

Clan MacIndoe

3rd Officer

|

8/1973

|

12/1973

|

|

Clan Grant

3rd Officer

|

12/1973

|

4/1974

|

|

Clan Ramsay

2nd Officer

|

9/1974

|

7/1975

|

|

Rothesay Castle

2nd Officer

|

8/1975

|

8/1975

|

|

Clan MacIver

2nd Officer

|

9/1975

|

10/1975

|

|

Clan MacGregor

2nd Officer

|

11/1975

|

11/1975

|

|

Clan MacNab

2nd Officer

|

11/1975

|

12/1975

|

|

Causeway

2nd Officer

|

10/1976

|

4/1977

|

|

Kinpurnie Castle

2nd Officer

|

7/1977

|

7/1978

|

|

King Richard

2nd Officer

|

12/1978

|

4/1979

|

|

Clan MacGregor

2nd Officer

|

6/1979

|

12/1979

|

|

Clan Alpine

2nd Officer

|

3/1980

|

8/1980

|

|

King William

Chief Officer

|

6/1981

|

6/1981

|

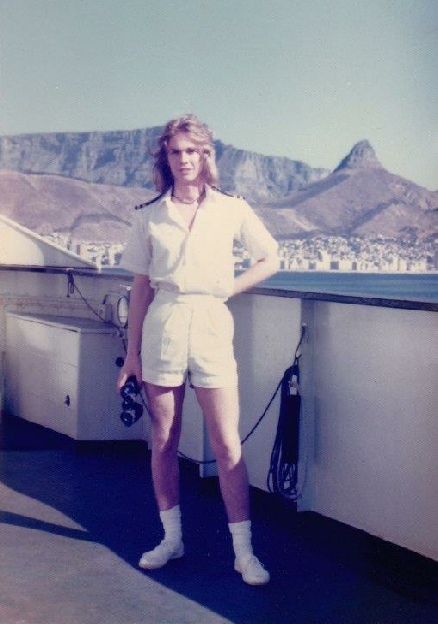

Photographed on Clan Ramsay by Andy Skarstein

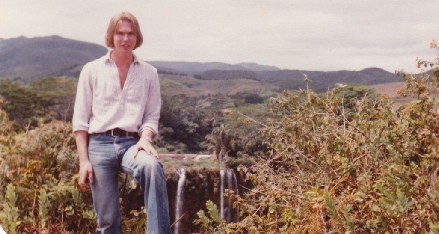

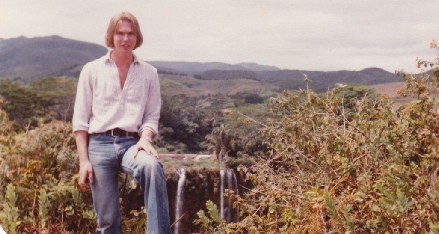

Hector Heron - 1972 - Cadet

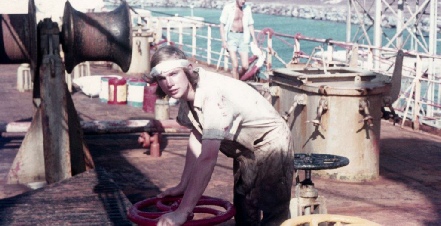

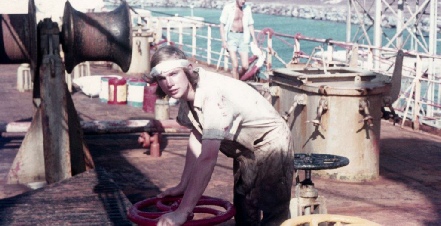

Mark swinging the valves during loading operations

Officers in their natural environment

Clan MacIndoe - 1973 - Third Officer

2nd Officer Ian Scott on the right

Clan MacIntosh - 1973 - Cadet

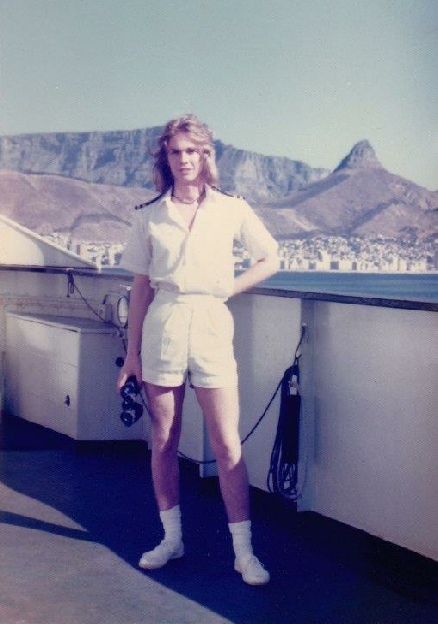

Kinpurnie Castle - 1977/8 - Second Officer

Broken topmast in heavy weather

King Richard - 1979 - Second Officer

With Colin Batty 3rd Officer

With Steve Collins - Cadet

Kinnaird Castle - Cadet - 1971

Alongside in Birkenhead prior to Mark’s first trip

Cadet Training Officer - Richard Mennell

3rd Officer Dick Thomas at a party on board

Cadet Nigel Hughes at a party on board

The Ship’s Cat - Name is missing from Crew List

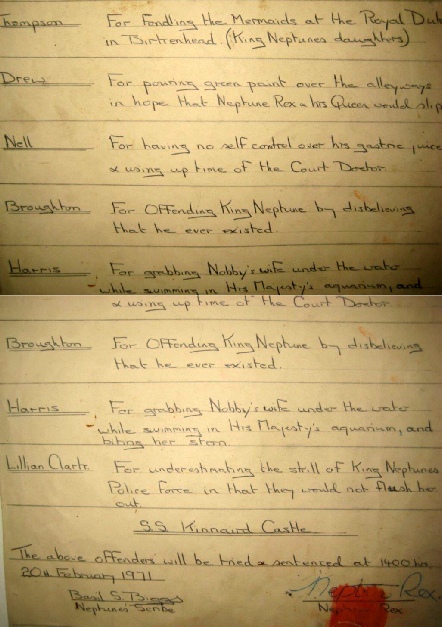

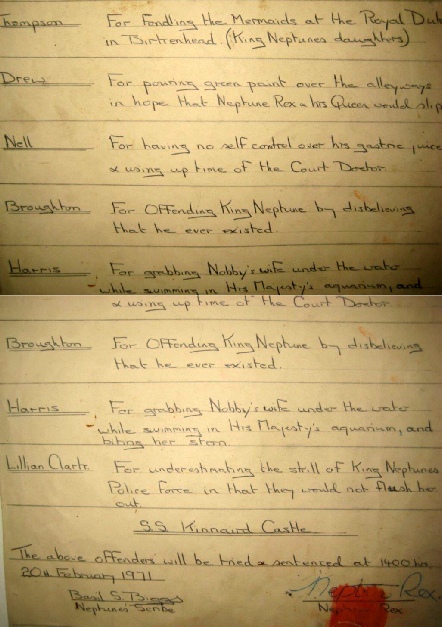

The list of trumped up charges alledged against first trippers

Pictures of The Ceremony can be found on the Kinnaird Castle page

Clan Alpine - 1980 - Second Officer

Boarding a lifeboat for a trip ashore at Mombasa

Captain Basil Biggs at the helm

John Watt 2nd Engineer, the wife of Electrician Nobby Clarke

and Captain Biggs

1. Change your underwear every day

2. Read a quality newspaper such as The Times or The Daily Telegraph

3. Don’t go out with girls who live in council houses

Probably grounds for prosecution these days. I also remember Capt Danny Richards (Master when I sailed on King Richard and a proud Yorkshireman) telling me that when he was Chief Officer, he wore a flat cap to the office while on leave and was told that he would never be given a command if he continued to wear it in public.

After a year at Warsash I was one of eleven cadets sent to join Kinnaird Castle in Birkenhead. We boarded the vessel on 8 January 1971 and sailed exactly one month later. We left Vittoria Dock at night and the training officer sent several cadets up forward and some down aft for stations. I was lucky enough to be one of three cadets Deployed to the bridge. The first cadet was instructed to write up the movement book and the second was shuffled out to the bridge wing as an extra lookout. When it came to my turn, I was fervently hoping I would be asked to swing the big, shiny brass telegraph at the front of the bridge which made an impressive jangling sound when you pulled the handle. When the training officer looked at me said “And you, Williams, have the most important job of all”, I grinned and started walking towards it. He then said, “You’re making the tea”. The darkened bridge was heaving with people when we left the dock – the Master, OOW, two pilots and various other worthies, and keeping everyone supplied with tea and coffee was a full time job. After we exited the lock and entered the river, the visibility began to deteriorate. I was rushing back to the chartroom with a trayful of crockery at one point when one of the pilots, who had been peering ahead into the gloom, stopped me and said “Young man, do you have any glasses?”. In my ignorance, and not being familiar with the colloquial terms for binoculars, I replied “Sorry sir, I’ve only got mugs”. I won’t repeat his reply!

Although we were loaded with cargo destined for East Africa and the Red Sea, we sailed via the Cape as the Suez canal was still closed to shipping. We were given various tasks during the voyage south to keep us occupied and I never want to see another chipping hammer again. A couple of days after we crossed the line, the training officer asked for volunteers to paint the lower alleyway decks inside the accommodation. He said that it had to be done at night when there were less people around and added that whoever volunteered could have the afternoon off. Eleven hands shot up and the training officer selected three cadets including me. We were shown where the green deck paint was stored and we spent an hour or so after lunch cutting-in around the edges before knocking off. Our plan was to start painting the alleyway decks with rollers at around 2000 hours and we reckoned that the job would take around 60 minutes. At 1930 it was announced that a film would be shown in the smokeroom starting at 2015 which those of a certain age will remember as being a big event in those days. Realising we would miss most of it, we started to panic. We needed to complete the job much more quickly so, in a flash of adolescent brilliance, we went back to our cabins and pulled on our seaboots. We then poured gallons of green paint on to the deck which we brushed around the alleyways with brooms. The paint seemed to disappear very quickly so we just kept pouring out more. We were all done by 2030 and after chucking the brooms over the side to conceal the evidence, managed to see most of the film. The following morning the training officer inspected our work and told us how pleased he was. We congratulated ourselves on our initiative. A few days later we called at Durban for bunkers and the Chief Officer took a walk along the quay to check the condition of the hull paintwork. He stormed back up the gangway in a rage, shouting obscenities and pointing at several large streaks of green paint running from the bottom of the accommodation down to the waterline. The ship resembled a sick zebra. We had no idea about shelter decks or the fact that they were fitted with scuppers and we were lucky not to have our shore leave stopped when we reached Mombasa.

Thinking back, the company looked after us very well during that first voyage. We were whisked away on jollies that included water-skiing, deep sea fishing, a safari, a trip on an Arab dhow and a brewery tour, all of which all seemed normal at the time. It wasn’t until much later that I came to realise how fortunate we were to work for a company that showed a genuine interest in the welfare of its cadets.

I also developed a real fondness for the ship given its traditional lines and the fact it was a steamer – much more character than the vessels built by the company later on. I now have a 3ft model of Kinnaird Castle on display at home although Jo, my wife, can’t wait for me to peg out so she can get rid of it.

It seems rather young these days to leave home for a seagoing career at 16 but I never thought about doing anything else. I may have been influenced by the many generations Cornish fishermen on my father’s side and growing up close to the sea in Plymouth, but it probably had more to do with wanting to leave school at the earliest opportunity.

Being completely clueless about the shipping industry, I applied to three different companies at random and was asked to attend an interview by all of them. The first was with Cunard which was a household name as the QE2 had recently entered service. At one point they asked me what action I would take if the QE2 had a power failure while approaching the berth in New York during a tug strike. Cunard had evidently set its bar for admission fairly low as they still offered me a cadetship after I said I’d check the fuses. I was then interviewed by P&O and B&C in quick succession. I was accepted by both, but shipping companies were recruiting in droves at that time and nothing short of buggering the Chairman would have constituted grounds for rejection. After a great deal of serious deliberation I decided to join B&C as they had curly braid and a nicer cap badge than the others.

I was sent to Warsash for a year’s pre-sea training and was paid a salary of £17 5s 8d a month (if you have to Google this, you’re younger than me). A few days after I started, all B&C cadets were required to attend an induction seminar given by one of the company’s training officers. He said that B&C had high expectations of us and that we should uphold the traditions of the company at all times, ashore and afloat. He then said that there were three important rules to follow if we were to have a successful career with B&C:

Having long hair meant that I never sailed on the mail ships, but it actually did me a favour. After a couple of trips as 3/O I was summoned to the office and the crew manager (Chris Abbott) was absolutely aghast at how long it was. He asked me to get it cut but I refused. He then went into a huddle with a couple of his colleagues and returned to say that rather that sending me to join another ship as 3/O as they’d planned, they’d promote me to 2/O if I came back to the office in an hour with shorter hair (which I did). He was as good as his word and I joined Clan Ramsay as 2/O a couple of weeks later. It didn’t take long to grow back!

I obtained my Master’s ticket in 1981 but given the rapidly shrinking fleet, it was no surprise to be made redundant towards the end of that year like so many others. I’d always preferred general cargo vessels to bulk carriers and tankers but their days were clearly numbered. It seemed like the right time to try and find a position ashore but it wasn’t easy without prior shore experience. At one point I applied for a marine officer’s job working in the control tower at Harwich and was interviewed by a panel of crusty old codgers, most of whom sported silver beards and an abundance of gold braid. Towards the end of the interview the chief codger gave me a stern look and asked “Mr Williams, do you consider yourself to be an ambitious person?”. A predictable interview question so I trotted out the standard reply about wanting to progress my career and get on in life. On hearing this he shook his head at his colleagues and said “Right, you’re clearly not the man for us then” and ended the interview.

I was eventually taken on by a trading company which specialised in chartering vessels to transport rice and sugar to Nigeria. They needed a Port Captain in Lagos to supervise their discharging operations but wanted to make sure I knew what I was doing before offering me the job. In order to test my skills they first sent me to Bilbao to load a chartered Freedom-type vessel with several thousand tonnes of palletised cubed sugar. It was a simple task, but a couple of days before completion I measured up the space remaining and found that there was no room for the last 200 tonnes. I phoned the chartering manager who was mortified at the prospect of having to pay deadfreight, so I suggested breaking open the pallets and stowing loose cartons between the beams right up to the deckhead to minimise the amount of broken stowage. Also, since it was summer, loading any remaining pallets on deck and wrapping them in canvas for the passage south. He grasped this suggestion with both hands and frantically told me to go ahead. The following morning I measured up again and it suddenly dawned on me that I’d cocked up my calculations the day before and there was more than enough room for the entire cargo. I told the stevedores to stop breaking open the pallets and we completed loading the next day with plenty of space to spare. I was so embarrassed that I said nothing to the company. However, rather than being subjected to a shameful inquisition when I returned to the office, I was warmly congratulated for saving the company from a significant financial penalty and thy offered me the job in Lagos as soon as I walked through the door.

Living and working in Lagos was a steep learning curve and a memorable experience. However, the following year I decided to move on and successfully applied for an Operations Superintendent’s job with a ship management company based in Kent. The company was owned by an overseas trading company which mainly exported bagged cement from Eastern Europe to Africa and the Middle East.

After chartering vessels for a while they decided to buy some old bangers and operate them on a shoestring with the cheapest foreign crews available. They set up the management company with a handful of very experienced and knowledgeable Master Mariners, all of whom had been around the block a few times. It was real seat of the pants stuff, and one never knew when arriving at the office in the morning whether you’d be on a plane later that day to sort out a problem that should never have happened in the first place. I spent two very happy years there and learned a lot. I left in 1984 to work for a Norwegian shipowner in London who was in the process of registering vessels in the UK to take advantage of the capital allowances scheme. I joined as Operations Manager and set up the company along with two others. Most were purpose-built ice class vessels designed to carry forest products and were equipped with a stern ramp and side doors. I became a director of the company in 1989 and subsequently relocated to the head office in Stockholm together with my wife and our children.

After living in Sweden for a couple of years I was approached by a major Protection & Indemnity (P&I) Club in London which was looking for someone to set up a Loss Prevention department. P&I Clubs provide marine liability insurance to shipowners and most operate as mutuals. It sounded interesting so I accepted their offer and we returned to the UK at the end of 1991. Marine insurance was not something I had ever considered as a career but I thought I’d give it a try for a couple of years and go back to managing ships if things didn’t work out. However, the position turned out to be quite a challenge and it wasn’t long before I was enjoying it. Far from being a desk job, much of my time was spent working with shipowners around the world to reduce their exposure to incidents and claims. I decided to stay and became a director of the Club’s management board in 1997, retiring in 2016.

Jo and I have travelled a great deal since then, but definitely not on bloody cruise ships!

Mark Williams

August 2020

PS: I had fun letting my hair grow down to my shoulders again during lockdown until our eldest son said that I looked like a badly dressed lesbian. It’s now been cut to a more respectable length, much to Jo’s relief.

Clan Ramsay - 1975 - Second Officer

Clan MacGregor - 1979 - Second Officer

Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List

Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List

Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List

Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List Crew List