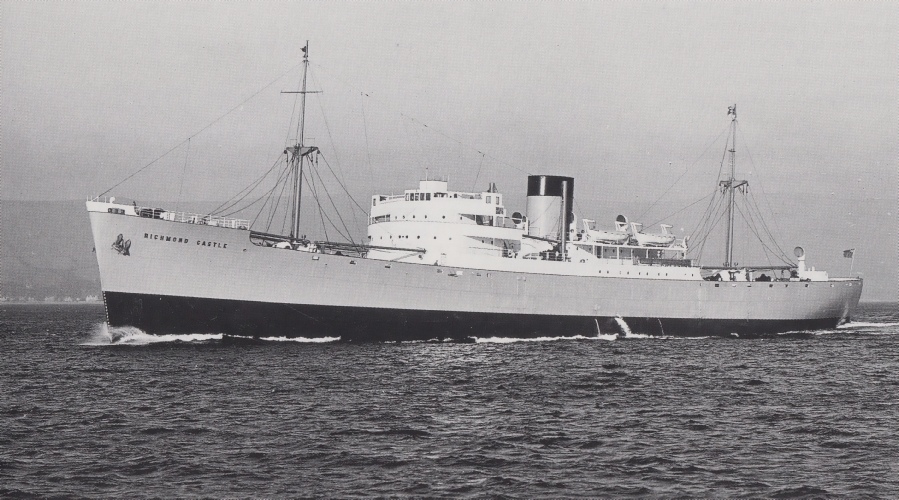

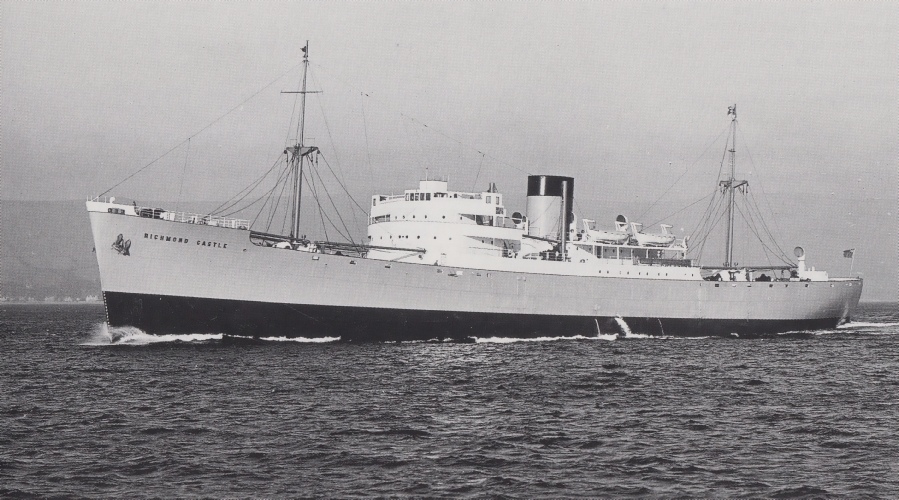

RICHMOND CASTLE (1) was built in 1938 by Harland & Wolff in Belfast with a tonnage of 7798 grt, a length of 457ft 2in, a beam of 63ft 4in and a service speed of 15 knots.

Sister of the Rochester Castle, Roxburgh Castle (1) and Rowallan Castle (1) she was delivered on 11th February 1939 and operated on the refrigerated fruit run

In August 1942 she was torpedoed and sunk by U-176 in the North Atlantic

Date of attack

4 Aug 1942

Fate

Sunk by U-176 (Reiner Dierksen)

Position 50.25N, 35.05W - Grid BD 1387

Complement

64 (14 dead and 50 survivors).

Route

Buenos Aires - Montevideo (18 Jul) - Avonmouth

Recollections of John Derrick Cutcliffe

The next voyage – to Argentine via South Africa again – passed off without incident. Our charmed life was not to last, however, and it was on the one following that when we were torpedoed.

We had sailed from Montevideo for Avonmouth on 18th July, routed independently as usual. We were struck by two torpedoes at 1125 on 4/8/42 in 50°25’N, 35°05W, about 750 miles to the east of Newfoundland, and the ship sank at 1132 (just 7 minutes later).

We learned many years afterwards, that we had been attacked by U176 under command of Lt-Com Reiner Dirksen, in fact we were first vessel to be sunk by U176 and by Dirksen. He and his U-boat were sunk with the loss of all hands on the 15/3/43 off Havana.

It gives me no satisfaction to write that. He was doing his duty just as we were, and I thought of him and his men during the unsuccessful rescue efforts last week in the Barents Sea.

Three out of our four lifeboats were launched, but one (No. 2 boat) capsized in the process and most of the equipment was lost. This boat was later righted and was the one in which I spent the next 9 days. No. 4 boat proved impossible to launch due to the heavy list. No. 3 boat was rescued on the 10th August by the “Hororatah” bound for Liverpool. In that boat 8 men died.

On the 13th August No. 1 boat was rescued by the “Irish Pine” bound from Halifax (Nova Scotia) to Kilrush in the Republic of Ireland. Four men, including the Captain, had died. Later on the same day, the Friday the 13 th August,

No. 2 boat – the one I was in - was rescued by the ‘Flower Class’ Corvette HMS “Snowflake”, which at the time was searching for the boats of the “Letitia”. Unfortunately their search proved unsuccessful, and they then took us back to their base port Londonderry.

All 17 of us in No. 2 boat survived, although it was ‘touch and go’ for several by the last day, and we would undoubtedly have lost men (as did the other two boats) had we not been rescued when we were. Don’t ever tell me that Friday 13th is unlucky!!

Not surprisingly, considering we had come through 9 days of severe weather and very testing conditions including a full Atlantic gale in a small ill-equipped open boat, some of the crew were in such bad shape when we arrived in ‘Derry’ that they remained in hospital for some while. I managed to hide most of my problems – I had 13 boils on one leg, 11 on the other and 3 on my right arm. Both feet were so swollen that I had to wear slippers which had to be cut open in order to get my feet into them - as I was determined to get back to my home in Ilfracombe, North Devon, just as soon as I could.

I started my long journey by train/ferry within a couple of days of landing there. It turned out to be not too brilliant an idea, as I had overestimated my reserves of strength and I only managed to get as far as London before I collapsed in a heap - literally. Luckily I had relatives there.

I was treated to the luxury of sleeping in cousin Nick's bed (he being off soldiering) and they took great care of me for a couple of weeks until I was strong enough to carry on homewards.

Our house in Ilfracombe was near the harbour, and when I did finally make it back home I went for a stroll down there. Sitting in his boat was an old sailor whom I had known all my life called Tom Souch who, when he saw me watching him from up on the quay, shouted up “Like to go for a sail, Sir?”.

There are no prizes for the best guess at my reply. He told me later that he had heard that I had been reported as “missing - presumed dead” and hadn’t recognised the rather wild unkempt figure who had shuffled along the quay and was looking down at him! In fact it took until well into October before I was sufficiently recovered to resume normal duty.

From the site of West Side Historical Society, http://www.ceats.org.uk

Angus Murray, South Shawbost and John Maclver, North Tolsta, were shipmates on the Union-Castle liner, Richmond Castle, homeward bound from the River Plate, when at mid-day on 4th August 1942 some 700 miles west of Newfoundland she was the victim of a U-boat. There was just time to launch the lifeboats before she sank. The torpedoes had blasted her side open.

Angus recalls that moment:

"ABOUT NOON there was a terrific explosion. Everything in my cabin fell in pieces around me. I was terrified till I remembered how the Lord had helped me previously. I recovered my composure and put on some warm clothing. I took my Bible, my two watches and my lifebelt from my locker and headed for the open deck. The sea was entering No. 4 hatch as I made my way with difficulty to the boatdeck.

I assisted in lowering the last boat as the ship heeled over, sinking. I shinned down a fall and swam to the lifeboat. It was waterlogged. We had to swim to a raft as the lifeboat capsized. It took quite an effort to right the boat and to bale her out. A lot of its equipment including the sails, food and water was lost. There were eighteen of us, including the Chief Officer, aboard. John Maclver was in another boat with the Second Officer. The Captain was in the third lifeboat.

The U-boat which had torpedoed our ship surfaced. They showed us great kindness, giving us food and field dressings for each boat and they told us the nearest landfall was Newfoundland. They waved good-bye to us as they submerged. It was decided that the boats should make for Newfoundland. During the night a westerly gale blew up and we lost sight of each other. It was bitterly cold. We fixed up a sea anchor with a couple of buckets, an oar and a rope which we recovered from among the debris floating on the sea where our ship had sunk.

Sometime during the following forenoon we sighted the other lifeboats. The Second Officer's boat approached us and told us the Captain was still heading for Newfoundland, but he himself was going to try for Ireland. They took us in tow as we had no sail. It was slow going, so after more consultation with the Chief Officer, I started to make a sail with blankets. I sewed two together with rope yarn. We hoisted this onto a ten-foot high flagstaff which we had recovered. It was crude but useful, as was a lugsail fashioned out of a 6 x 3 foot piece of wood with an oar for a mast. In fact it worked so well that we were going as fast as the other boat so we decided to sail independently. Before parting, the Second Officer shared food with us as we were running short and anticipating a three-week sail to land. We soon lost sight of each other.

At first, water was rationed to an ounce three times a day. Fortunately we recovered two tanks from floating rafts and this enabled the rations to be doubled. We also managed to collect some rain water to supplement our supply. During the night when I was at the tiller, I used to catch a few drops of water from occasional showers by holding a square tin-lid against my cheek. Even a few drops revived me.

As the days passed we seemed to be making good progress. However, we could only guess at our speed. Daytime was not too bad, but it got very cold at night. We rubbed each other's hands and feet with oil to restore circulation and generate a bit of warmth. The daily water ration was the main thing we looked forward to, though we also took a little food.

On Sunday, the sixth day in the boat, the sea and wind got up during the night when I was on the tiller. I remembered lessons taught me in my younger days when sailing open boats at home. One of these was that it was dangerous to run before the wind with too much sail. So we set a sea anchor. We began to ship water. I advised running on with only one blanket up. This worked and by next morning the weather had moderated a bit and we resumed progress at a fair speed.

Now and again I tried to read my Bible but the pages had got soaked and were unreadable. I prayed silently for myself and for my shipmates.The following Thursday we sighted a small speck on the horizon. At first we thought it was a U-boat conning tower. As it approached we saw it was an RN corvette. What a welcome sight! She was soon alongside with her crew helping us aboard. Our wet rags were discarded and we were wrapped in warm blankets and provided with all our other immediate needs. Our rescuers had been searching for survivors from another vessel when they spotted our boat. That is the way of the sea. A few days later we were landed in Londonderry."

JOHN MACIVER'S ordeal was still going on in the second lifeboat where he was playing a similar part to Angus's in sailing the boat. Here again his earlier experience in the Lewis open boats was providing a key role. It was some days later that rescue came to them. This was too late for several of them. Out of the original eighteen in this lifeboat only seven very exhausted men were left, suffering from the intense cold and exposure. By a strange coincidence the rescuing ship was one on which John had previously served and he received a particularly warm reception from former shipmates as he was helped aboard the SS Suffolk.

It was no more than their due when Angus and John were each awarded the British Empire Medal for "skill and resource in bringing survivors to safety in circumstances that would have daunted the bravest".

Sad to relate, John Maclver died soon after receiving his award. He never really recovered from his punishing experience. In recent years survivors from Angus's boat have had joyful and thankful reunions.

Torpedoed and Sunk in The North Atlantic - 1942

Survivors about to be rescued by HMS Snowflake

Cargo

5250 tons of frozen meat

History

Completed in February 1939

On 20 Jul, 1941, the Richmond Castle was damaged in a collision in 01°30N/41°54W with the British steam merchant Bangalore (6067 tons), which was shelled and sunk the next day by a warship in 00°59N/43°W.

Notes on loss

At 15.58 hours on 4 Aug, 1942, the unescorted Richmond Castle (Master Thomas Goldstone) was hit by two of three torpedoes from U-176 and sank after capsizing southeast of Cape Farewell.

The Germans questioned the survivors before leaving the area. 14 crew members were lost.

The master, 44 crew members and five gunners were rescued:

The master and 14 survivors by the Irish Pine and landed at Kilrush.

The chief officer and 16 survivors were picked up after 12 days by HMS Sunflower (K 41) (LtCdr J.T. Jones, RNR) and landed at Londonderry.

The remaining 18 survivors were picked up by the British merchant Hororater and landed at Liverpool.

(Although Uboat.net site states that the Master Capt Goldstone was rescued other information states that he was lost)

|

Master

|

From

|

To

|

|

H H Rose

|

2/1939

|

4/1939

|

|

J Lecky

|

5/1939

|

7/1940

|

|

T W McAllen

|

8/1940

|

11/1940

|

|

H H Rose

|

11/1940

|

12/1940

|

|

L P Wilkie

|

12/1940

|

1/1942

|

|

H A Deller

|

1/1942

|

4/1942

|

|

G H Pickering

|

4/1942

|

6/1942

|

|

T C Goldstone

|

6/1942

|

8/1942

Killed

|

Crew List

|

Vessel

|

Built

|

Tonnage

|

Official No

|

Ship Builder

|

Engine Builder

|

Engine Type

|

HP

|

Screws

|

Speed

|

|

Richmond Castle (1)

|

1938

|

7798

|

167169

|

Harland & Wolff

Belfast

|

Motor 8 Cyl

Burmeister & Wain

|

8000 BHP

|

1

|

15

|

Career Summary