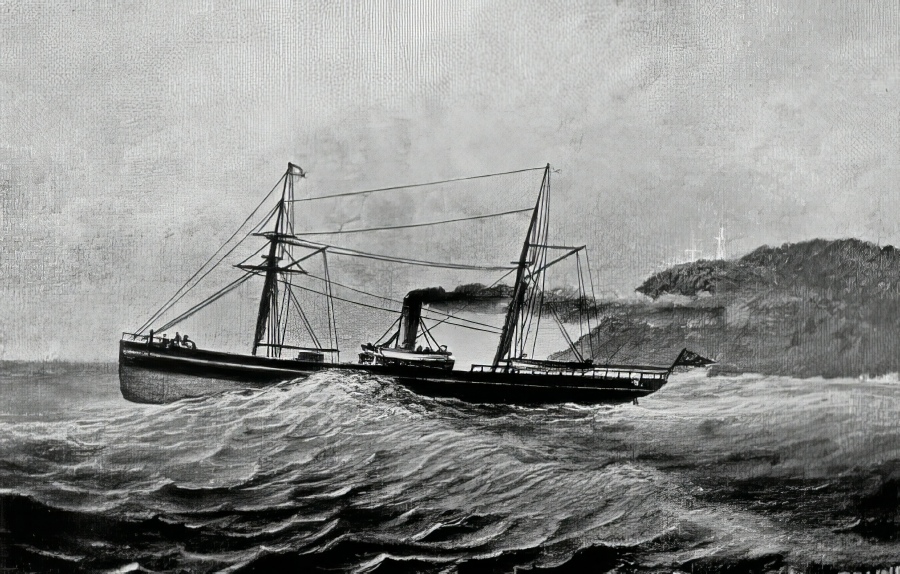

KAFIR was built in 1873 by J. Key at Kinghorn, Fife with a tonnage of 982grt, a length of 249ft 7in, a beam of 28ft 10in and a service speed of 10 knots.

Built for the South and East African coastal routes she was wrecked at the entrance to Simonstown near Cape Point in February 1878.

Owned by the Union Line, the S.S. ‘Kafir’ under the command of Captain Ward sailed from Table Bay on the Wednesday, the 13th of February 1878, on a voyage that would take her to all the coastal ports to Port Natal, then onwards to Mozambique and Zanzibar, a voyage the ship, and the master, had made a number of times.

Around tea time on that day she struck a rock off Oliphant’s Bosch, close by Cape Point. Within minutes she was flooding, Captain Ward immediately decided to beach the ship, thus saving the passengers and all but four of the crew. The ‘Kafir’ by the following morning had broken her back. Today nothing remains of her. These are the bald facts.

Of great interest is the navigation and ship management procedures that came to light at the official inquire that was conducted within days of the loss, for they clearly demonstrate what today we would consider an appalling lack of competence and responsibility, but was, in 1878 considered the norm. (See the circumstances of the loss of the Celt’ (2) a little further along the coast.)

As with the loss of the ‘Celt’ three years earlier off Quoin Point, the compass played a crucial part, as did the almost casual regard to the vessel’s position. Such a condemnation is entirely unfair, for we cannot judge the seaman of 1878 to those of the twenty-first century. Their knowledge of the mechanics of the magnetic compass was virtually nil, not even the master understood how the ship’s head affected the compass deviation. Neither did they fully understand how deviation could be altered by other external influences, such as the cargo, even the metal of a sheath knife the helmsman almost certainly had on his belt!

To us it is astonishing that neither the vessel’s course, nor position, from compass bearings or even a simple dead reckoning, were recorded. Neither was there a chart on the bridge available to the officer on watch. Both these deficiencies to our minds, were common to both the Celt and Kafir’s strandings.

By even the standards of the day, the casual attitude of the master and watch keepers to the navigation of the ship beggars belief. The master rounds the breakwater, sets a course by eye down the coast, even quartermasters have only a general idea of the course they should be steering, none of the officers think it necessary to even make a rudimentary attempt to fix the vessels position, to use their own words, they navigated by eye!

Were they negligent or simply over confident in their own ability? Once the ship struck the reef, the master and officers all showed superb seamanship and ability. In steadily worsening conditions, with the ship breaking up about them, the only lives lost amongst a total of some hundred and fifty or so people (the chief officer was remarkably uncertain of the number of passengers on board) were the four crewmen who drowned, and you could say they were the architects of their own fate. Very few comparable examples will be found of such ability. It may be thought that the master ran a very lax ship, but this is not supported by the iron discipline and control shown by the master and officers in the face of disaster. So who are we to judge?

However there was one rather telling omission on the part of Captain Ward, one that may indicate that he knew his defence was weak. One of the first things a master, confident his conduct would bear scrutiny saves, is his log book and charts, for they are vital and indisputable documents in his defence. Surely Captain Ward would have saved these?

Journalists of the day could never be accused of using one word where two or more were available! But lacking photography, they painted fascinating and detailed word pictures recording events, an art almost completely lost. The graphic word picture of the stranding, panic amongst the passengers, conduct of the officers and crew, is a model of its kind. The following are taken from the ‘Cape Argus’, the South African Library, Cape Town.

There are a few places where I suspect the type setter made errors, but in only one instance have I suggested an alternative word, otherwise what you see is the article as it was printed.

****************************************

Cape Argus, Thursday February 14, 1878

THE “KAFIR” ASHORE.

Just as we were going to press we received the startling intelligence that the Union Company’s steamer Kafir had gone ashore at Oliphant’s Bosch, near Cape Point. No particulars were ascertainable beyond the fact that the passengers had been landed, and that assistance was required. Further details will be published as soon as known. The Kafir left yesterday, shortly after noon, for Zanzibar and the intermediate ports.

Cape Argus, Saturday, February 16, 1878

Wreck of the “Kafir”

DETAILS OF THE DISASTER

Since the memorable wreck of the Windsor Castle no marine disaster on the coast of South Africa has occasioned such a thrill of excitement and, sympathy as the loss of the Union Company’s coasting steamer Kafir, the news of which was first announced in the regular issue of the Argus on Thursday.

It will hardly be necessary to repeat, except by way of introduction to the narrative of this sad misfortune, that the Kafir left Cape Town on Wednesday last for the east coast ports and Zanzibar. She was appointed to start at noon, but there were several passengers booked who arrived at the docks late. Among these was Messrs. J. and P. Meiring, with Messrs. J.P. Swemmer and H. le Roux, who had come down from Mossel Bay, the former two as litigants, the later as witnesses in a case in the Supreme court.

They waited for the conclusion of the case, thus the ship was detained chiefly for these passengers, until a quarter to two, at which time she steamed out of dock and …… of Table Bay with fine weather and a gentle north west breeze. The late passengers were … for being the unavoidable cause of the ship’s detention, and Mr. Meiring, who had been the successful litigant in the case in court, promised to ‘treat’ the ship. Added to the favourable beginning of fine weather there was a smooth sea, and the ship went along in what is commonly understood as “fine style”.

She rounded the Point, and steered along the wall of land to Cape Point, and as she went the breeze freshened, the first light clouds of the day moved over from the sea, and the waves began to put the ship in a moderate rolling motion. A few of the passengers had gone down to their berths from the susceptibilities to which most mortals are liable at sea, but the heaving of the ship was not yet violent, and the greater part of the passengers were either on deck watching the last of the mountains, or chatting in knots in the saloon or cabins below. While the breeze still freshened, and the sun was being obscure by increasing masses of scurrying clouds, some of the passengers who had been on coast voyages before, remarked that they were sailing rather close to land. Others old in experience on the coast replied that they had frequently run much nearer this strip of land. These, however were only opinions of the passengers, and would have been of no moment, even among those who expressed them, had not the consequences ensued which are to be recorded.

In what position the ship was at this time – about five o’clock – has not yet been ascertained, but the locality has been stated by one of the officers as the Albatross Reef off Olifant’s Bosch. Captain Ward who with most of the ship’s officers, was on deck, had just been speaking to a lady passenger upon the circumstances attending the loss of the European, when, with the suddenness of a gunpowder explosion the steamer was staggered by a shock, the effects of which could accurately be described in the statement that all on board were startled. One gentleman who was going up the companion-way was hurled back, and carried two men off their feet with him. Another who was standing by a lady’s seat was thrown right over both her and her chair; and a third was prostrated from a thump received on the head striking against a cabin. Such, with the rattling of dishes, the capsizing of heavier articles, and the occasional exclamations from passengers, were the accompaniments of the first crash.

The steamer was brought well-nigh to a total stop for the moment, and the expression of a passenger was “It seemed as if the earth itself was suddenly at a stand still.” Officers ran from post to post in their respective duties, and most of the passengers, with alarm in their faces, sought their friends, or eagerly inquired what was the matter. The steamer seemed to reel from the confusion of the shock, and gave a light lurch. As she rolled the cap of a wave slapped against her, throwing a dash of spray over the decks, till now dry, and as the swell came up she lifted quite clear of the rock on which she had struck, and moved ahead again. This was about 5.15.

After the first panic the passengers were surprised to find how cool the officers and sailors were, and self-possession soon returned to all. Looking astern the water could be seen to be discoloured beneath the surface, and there was a whirlpool indicating the rock on which the ship had unfortunately settled between two waves. Had she rode over a moment sooner or later she might have cleared the reef on the waves crest and have passed safely on. About five minutes or so after the shock the engines were stopped.

On examination of the state of the ship, it was found that water was literally pouring into the fore compartment, and into the “collision bulkhead”, further amidships. It took but a few minutes longer to realise that the damage was serious and the captain very wisely decided to put for the shore, seeing he was yet several miles off Simon’s Town. It happened that they were now just off a cove, to which the fisherman of Simon’s Town resort for fish. All steam was put on, and the boat brought towards the land, she being apparently two miles off. The ship fairly trembled under the pressure, and the shore was rapidly neared. The surf cold be seen breaking ahead, but the land was low at this point, and it was thought there might be a good depth of water to near the projected landing place.

Once however a slight bump told of a rocky bottom, and when between a half a mile and a quarter of a mile from the shore, two or three shakings were felt, and she grounded on the rocks. In the first compartment the water was now three feet from the deck, and as she went aground the abrupt stoppage caused the water to flow forward in the engine room. The fires were put out, and a cloud of smoke, steam and soot, belched forth, blackening the faces of those on deck.

In the meantime two boats were being got ready to land the passengers. One was let down and ropes were procured to put off a boat load, the steamer working gradually round the waves. Just then there was some confusion. A number of men, rather heedless of the claims of the claims of women and children made a rush for the boats. Two men in particular entered into a struggle on deck. A dog went to the assistance of one of them, but a St. Bernard dog of a nobler nature stepped in and settled matters with the other canine, and was it was said, the means of bringing the other contestants to their reason.

The captain and officers restored order, and commanded some of the men to let the women go off first. The ladies were let down with ropes, and acted generally with good sense under the operation. To hasten the embarkation the sailors cut the ropes as the ladies and children were let down, instead of untying them, and in short time the boat load manned by black and white sailors, containing about a dozen women and children rowed in. Providentially a small bight of about fifteen feet was located right ahead and avoiding the ugly rocks which protruded everywhere else around it, they steered to this. Just as they entered the narrow mouth a retreating wave came, and with the dashing of the waters against the rocks on all sides the poor sailors threw down their oars in despair. “Pick them up again!” yelled the officer in command, and those that had not lost their blades did so. The succeeding wave, coming just in time, assisted their exertions, and they shot in with one pull till they came on the rocks in the comparatively quiet and weedy waters inside. But the boat was now nearly swamped, and the ladies sat up to their knees, holding the children out of the water. The men jumped out up to their necks, and carried the women and children in on their backs.

They were all out safely and quickly put on dry land. During this time the second boat alongside the steamer was awaiting orders, and the first load succeeding so well, the discharging was proceeded with. This boat landed with similar adventures and success, taking ashore all the more frail and helpless portion of the passengers. All this time the wind and the waves were increasing, and the ship now broadside to the seas was pounding on the jagged rocks with every coming swell. The boats made three trips out again, each time taking off a few men.

Wreck of Kafir at Simonstown - 1878

Master |

From |

To |

|

A Garrett |

2/1875 |

|

|

Ward |

|

2/1878 |

|

Vessel |

Built |

Tonnage |

Official No |

Ship Builder |

Engine Builder |

Engine Type |

HP |

Screws |

Speed |

|

Kafir |

1873 |

982 |

68825 |

John Key & Son Kinghorn |

John Key & Son Kircaldy |

Compound Steam |

139 NHP |

1 |

10 |

Career Summary

Kafir