The enquiry commenced on the following statement of case:

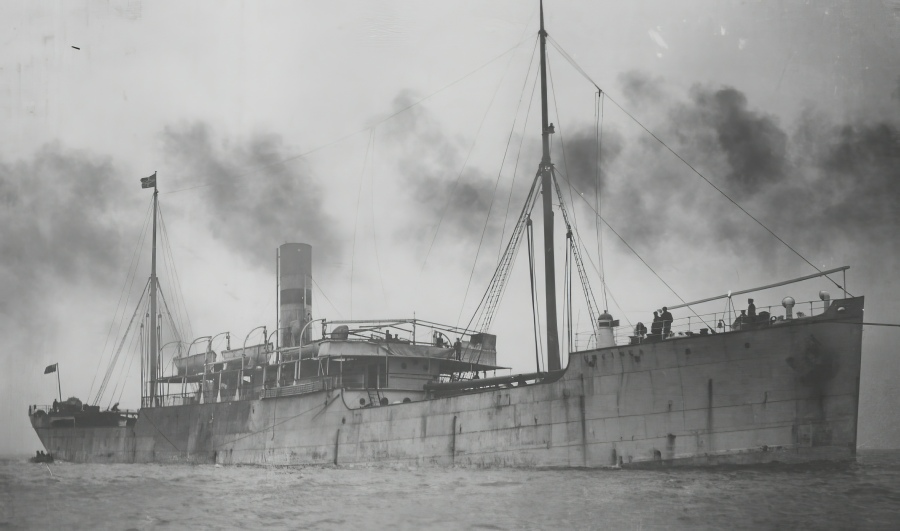

The s.s. "Umsinga" left Port Natal at 6.5 p.m. on Saturday, the 31st March, 1906, proceeding on voyage from Natal to Delagoa Bay. The steamer struck on Tenedos Shoal, and in consequence returned to Port Natal, arriving in a damaged condition at 3.20 p.m. on 1st April, 1906.

The first sitting was held on the 4th day of May, 1906, and the following witnesses were examined:

Lewis Richard Mann; Nicholas Chiazzari; Daniel Lewis; John Letts; John Jervis Gerrard; John Brady.

The Court resumed on the 7th day of May, 1906, when the following witnesses were examined:

George Kamph; Robert Luhman; Charles Buckley; Alexander Angelinorff; Percy Rae; John Letts (recalled); Charles Buckley (recalled); Daniel Lewis (recalled); John Henry Munro.

On the 8th day of May, 1906, the witnesses for the enquiry having been called, it was intimated from the Attorney General that, as a result of the evidence which had so far been taken, it was necessary that charges should be framed against the master, and certain of the officers, and, on the 14th day of May, 1906, the charges having been received, the Court adjourned until 10 a.m. on the 17th day of May, 1906, in order that the requisite period of notice might be allowed to the persons charged, and every available opportunity given for defence.

Copies of the original case for enquiry, and of the charges, were duly served upon the master, the first mate, and the third mate. A copy of the charges against these gentlemen is annexed to this report.*

The enquiry, therefore, was continued in the form of an investigation into the charges against the persons named, and the whole of the evidence, which had already been given in the enquiry, was again given afresh, in connection with the charges, it being agreed by all the parties and counsel concerned that this course should be followed.

At the conclusion of the evidence for the Crown, counsel for the persons charged were asked whether they had any further evidence to bring in defence, and that, if such were the case, the Court was willing to adjourn for any reasonable time, in order to allow such witnesses to be forthcoming.

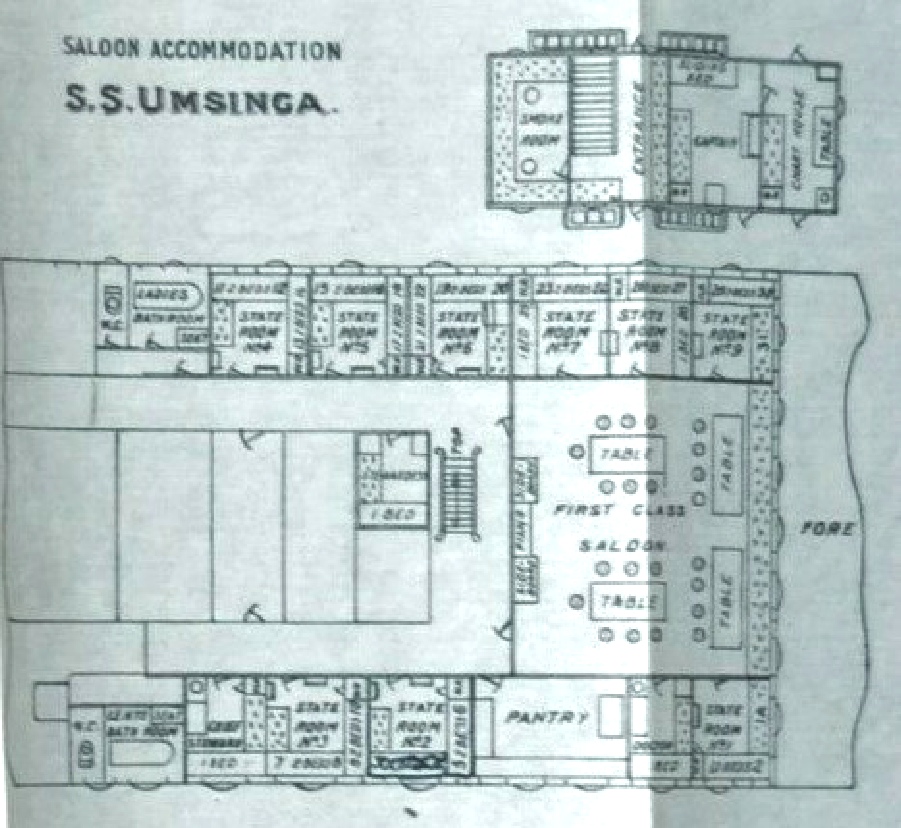

The s.s. "Umsinga" left Durban on the 31st of March, 1906, on a voyage to Bombay, via Delagoa Bay, with a part of the original cargo laden In London, and about 120 passengers for Bombay.

The pilot left the ship at 6.10 p.m., outside the bar.

The master set the course at N. 45° E., by compass. The deviation of the compass would appear to have been looked upon as so small that it was disregarded, but it is found recorded in the deviation-book to have been 2° E. on that quadrant.

The vessel was supposed to be making 10 knots but this had not been verified by record from the log.

The master seems. according to the evidence, to have left the deck at 7.15 p.m., and there is no record of his returning until after the casualty.

The last course given by the master was N. 45° E. which, if continued for one and a half hours, would have put the vessel ashore, but he verbally instructed the chief officer, who took over charge from him, to keep a good distance off the land.

It was stated that the course was changed at 7.15 p.m. to E.N.E., but neither of the log-books are definite on this point.

At 8 p.m. the chief officer went below, and was succeeded by the third officer, J. R. Letts, who has held a second mate's certificate for a period of seven months, and he received verbal orders from the chief officer to keep the vessel a good distance off the land, the course then being E.N.E. by compass.

During the period of his watch, the course was altered several times, but the evidence of the helmsman and the officer are in conflict as to the extent of the alterations.

At midnight, however, the course was given to the second officer, on his assuming the watch, as E.N.E.

Seven minutes afterwards the vessel struck, and remained aground for two and a half hours, bumping heavily. She then came off, leaking badly, and returned to Durban. She has since been on the floating dock, and has been temporarily repaired, but the injuries have been so extensive that it will be necessary for the vessel to be sent to England for permanent repairs.

From the evidence adduced, it was evident that, from the moment the master assumed control from the pilot, no steps were adopted to ascertain the position of the vessel, by taking cross bearings of lights for a departure, nor was any attempt made to verify the correctness of the compass, or to take the time of the dip of the Bluff light, and its bearings.

No course was laid down on the chart, nor were any instructions left with any of the ship's officers, either verbally or otherwise, as to how far the ship was to run by the log before changing the course, nor were any instructions given as to what the course was to be changed to from time to time.

None of the officers were made familiar with the contour or trend of the coast, nor were they warned of the dangers existing, in the shape of such dangerous shoals as the Glenton Reef and the Tenedos Shoal, which they would necessarily pass during the night.

The third officer, with his short experience, was left from 8 to 12 p.m. in charge of the navigation of the vessel, with no knowledge of the coast or the charts appertaining thereto. He was not even instructed when to call the master, or informed of the dangers he was likely to meet, the courses being left entirely at his discretion.

Only two able seamen were on deck, one at the wheel and the other at the look-out. This meant that one of these men had to leave an important post, if any essential duty about the decks had to be carried out.

It is on record, and it is regrettable, that the man on the look-out left his post to call the watch below just at the time when, if he had remained at his post, he would most probably have observed the breakers in time to have warned the officer on the watch of the danger.

The records of a former voyage were on board, and from these the master could have ascertained the course by which the vessel had then been navigated in safety past the points of danger, but these were not availed of.

Lord Kelvin's patent lead was on board, but no use was made of it probably because the number of hands on deck during the watch were not sufficient.

At midnight, the ship had, so far as can be ascertained, run 65 miles from Durban.

The assessors have taken the courses and distances as they appear in the log-book, and as sworn to by the witnesses, and, after laying them off on the Admiralty chart, it is found that these courses place the ship where she struck, viz., either on the Glenton Reef or the Tenedos Shoal.

It is a most extraordinary fact that the navigation of the vessel, after the master left the deck, should have been conducted under such conditions, that the safety of the vessel and of her passengers were practically entirely dependent upon the eyesight of the officer of the watch for the time being, and this at night. The absence of a night order-book is only one more instance of the laxity which seems to have prevailed.

The Court finds that L. R. Mann, the master of the steamship "Umsinga," during the voyage from Durban up to the stranding of the said vessel "Umsinga" on or near the Glenton Reef or the Tenedos Shoal on the night of the 31st March, 1906, was guilty of misconduct in having navigated his vessel in a careless and unseamanlike manner, without taking the necessary precautions, in consequence whereof the said vessel stranded, as. above stated, and suffered considerable damage, the lives of the passengers on board also being seriously endangered. The Court therefore suspends his. master's certificate for a period of six (6) calendar months, from the date of the casualty.

With regard to D. R. Lewis, the chief officer, the Court finds that, during a portion of his watch, which, however, ended at 8 p.m., the course steered having been towards the land he should have taken bearings of available lights, and should have fixed the vessel's position on the chart at 8 p.m., or should have reported the courses, distances, and bearings of lights to the master. He should also have conveyed to the third officer a more safe outside course, having regard to the third officer's inferior position, and inexperience. The chief officer is cautioned against displaying a similar want of diligence or care, but his certificate will not be dealt with in any way.

With regard to the charges against T. R. Letts, the third officer, this officer, on taking charge of the bridge, should, by enquiry and by consulting the charts and navigation books available to him, have made himself more conversant with the coast, its trend and outlying dangers, and be should not have been satisfied with the instructions merely to keep the vessel a safe distance off the land. He also would have acted with greater prudence and seamanlike care and skill had he conveyed to the master, from time to time during the watch, the course the vessel was steering, and the distance run according to the log, especially when the ship's head was altered by him to N.E. by E. 1/2° E., and N.E. by E. 3/4° E., by compass, and when the land became invisible.

The records of the courses steered, and other data connected with the conduct of the vessel, during the watch, are entered in a scrap log in a manner which reflects carelessness, and want of method.

Having regard to all the circumstances, however, the third officer's certificate will not be dealt with, and will be returned to him.

PERCY BINNS,

President.

CHARLES REEVES,

Assessors.

W. BROWN DICKIE,

(Issued in London by the Board of Trade on the 6th day of July, 1906.)