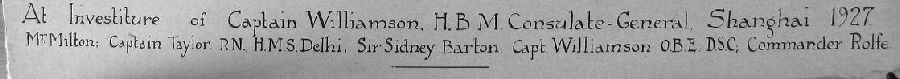

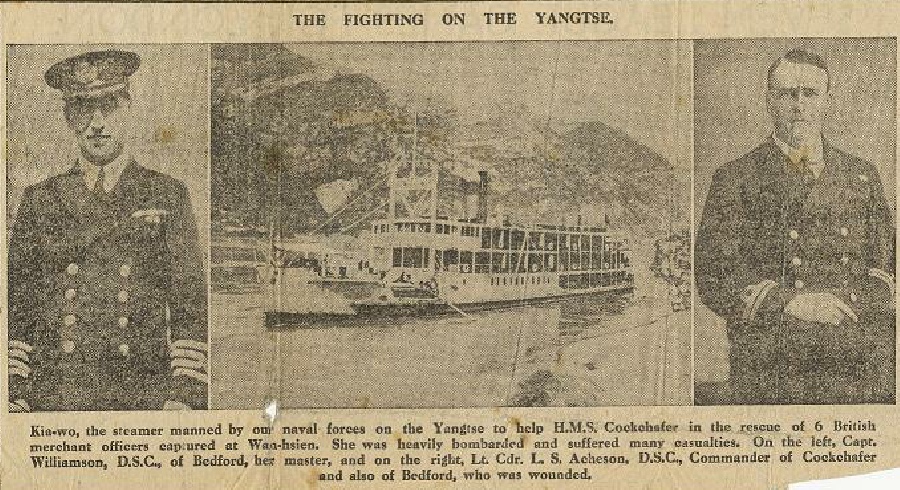

A. R. WILLIAMSON

Master and Marine Superintendent, Indo-China Steam Navigation Company Limited 1920-1946

by Himself

1906 to 1914 – Merchant Navy Steam and Sail World-wide

My decision to go to sea was taken in 1906, at the age of 15, when my father's business was at a low ebb. My ambition to serve in a sailing ship was sparked off by the example of a distant relative who was then First Mate of the Barque Silver How. At that time steam was fast supplanting sail and I was unable to obtain a berth in a deep-water sailing ship except at a premium which my father could not afford. However through the good offices of a schoolmaster with shipping connections I was offered an apprenticeship, without premium in the King Line of tramp steamers. I was therefore indentured to this company for three years, the wages being £5 for the first year, £8 for the second year and £12 for the third year. Apart from this meagre wage the Company provided the apprentice with nothing—not even bedding or mess utensils—except food on the minimum B.O.T. scale and of indifferent quality.

In September 1906 I joined the new steamer King Howel in Penarth in the Bristol Channel. Just arrived from the builder's yard on the Tyne, she was an ordinary coal and grain tramp steamer, carrying about 5,000 tons deadweight, of a type built in large numbers in the early part of this century. They were so similar that they were said to be "built by the mile, cut off by the fathom and the ends hammered in". They were strictly functional with a maximum speed of about 8½ knots. There was no electric light or power and the only aids to navigation on board were one chronometer, two compasses, one sounding machine and a patent Log. With this minimal equipment they roamed the seas of the world.

On her maiden voyage the King Howel carried a cargo of bunker coal to the Argentine Naval Base in Bahia Blanca, south of the River Plate, and returned with a cargo of Argentine grain to Antwerp. She was thereafter employed during my apprenticeship carrying coal from Bristol Channel ports to the Mediterranean and thence to the Black Sea for grain, or to India for a general cargo.

In the autumn it was customary for the tramp steamers to load coal for River Plate ports and return with Argentine grain. This arrangement was highly approved of in the half deck for we avoided the discomfort of unheated quarters and inadequate clothing in the wintry seas of northern latitudes by steaming to the southward to enjoy tropical heats and the summer sun of the southern hemisphere. It was therefore with howls of dismay that we greeted the news, received in the late autumn of my third year on board, that we were to load coal for the Adriatic ports and proceed thence to the Black Sea for grain. Fully loaded we set out on the worst voyage I made in the King Howel.

After being blown away from the quay in a Bora (strong northerly gale) in a small port south of Fiume (the modern Rijeka) we arrived off Ochakov, in the Black Sea, early in December. The whole country was under snow and ice—the cold was intense. We were bound for Nikolayev about 20 miles up the River Bug which was frozen over. A powerful ice-breaker preceded us to our loading berth and periodically churned up the ice alongside to enable the stem and stern draught marks to be read during loading. We rigged up a minute coal stove in the half deck but nevertheless conditions on board were most uncomfortable. Two days before Christmas, being fully loaded, the ice-breaker preceded us down river and clear of ice. The icy haze, however, made visibility very poor, the channel buoys had been removed on account of drifting coastal ice, the steamer got out of the fairway, ran aground on a mud bank and stuck fast. Tugs were sent to us but failed to move the vessel and we had to discharge about 1,000 tons of grain into lighters before she could be refloated. We then ran into Odessa harbour, reloaded the grain and sailed, finally, late on New Year's Eve. Early on New Year's Day the cook went aft to fetch the geese which the skipper had bought in Nikolayev to be a Christmas treat for all hands. On December 25th, however, we had been fast aground and hard at work, therefore the geese were left hanging in an empty locker on the poop pending a more fitting occasion. But they did not, after all, provide us with a New Year feast; they had been stolen by the Odessa stevedores. So we dined, as usual, on salt pork thinking hard thoughts the while about those Russian thieves. But we soon forgot our disappointment—we were, at last, homeward bound.

My indentures having expired, I left the King Howel in the autumn of 1909, having still to serve a further 12 months before the mast to complete the minimum four years then required to qualify a seaman to take the examination for a Foreign-going Second Mate's Certificate.

His own account of the rest of his career and the story of the “Wanhsien Incident” can be found at: Naval History Homepage.

After his retirement from Jardine Matheson & Co Ltd in 1947, Capt AR Williamson researched and wrote articles on the early personalities and ships of his company. These were published one by one in the company's Christmas newsletters. Eventually they were published all together for 'private circulation' in the book 'Eastern Traders'.

Albert R. Williamson

OBE DSC